Commentary by Gracelin Baskaran

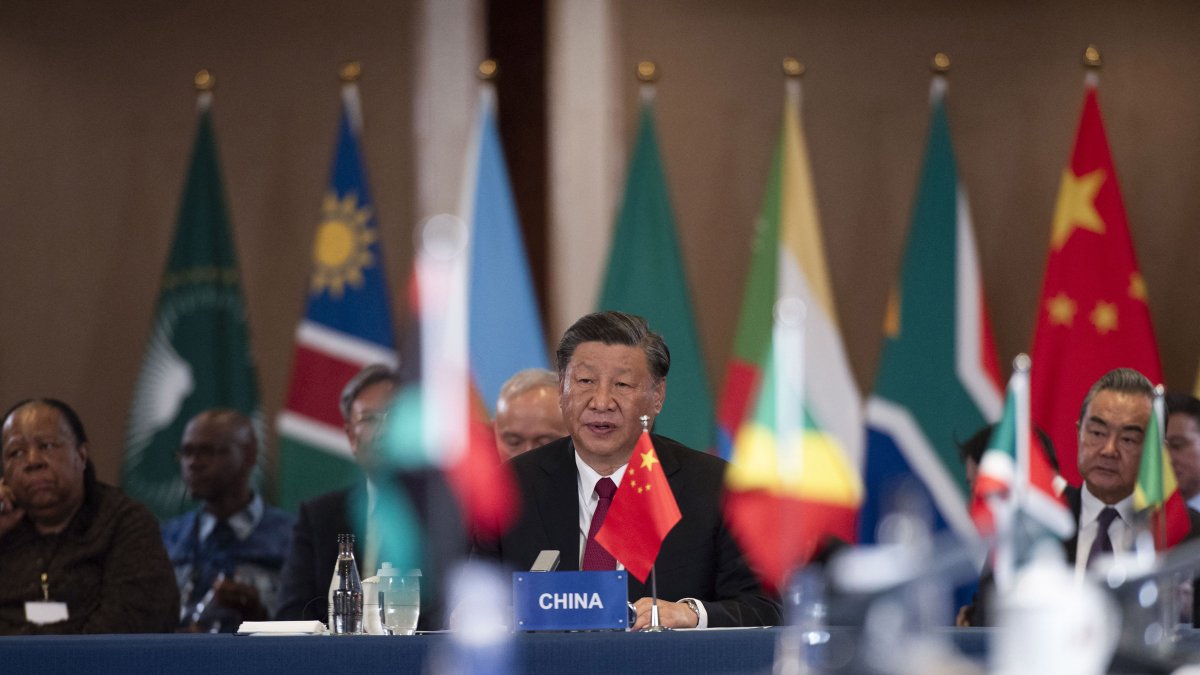

China is a few decades ahead of the United States in its commercial diplomacy efforts on the African continent. Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) increased from $75 million in 2003 to $4.2 billion in 2020. The value of trade between China and Africa has risen from $10 billion in 2000 to a record $25 billion in 2021—over quadruple the increase between the United States and Africa.

Chinese investment has been heavily concentrated in the extractive sector. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where roughly 70 percent of the world’s cobalt is produced, Chinese firms owned or had stakes in 15 of the 19 cobalt producing mines after a U.S. firm sold one of the DRC’s largest copper-cobalt mines to a Chinese one in 2020.

Can the United States—or even the larger bloc of Minerals Security Partnership countries—catch up or become a competitor? It’s not too late. African countries across the continent are growing weary of China’s exploitive approaches to economic statecraft.

The Resource-Backed Loan Model

Resource-backed loans (RBLs) are given to a government or a state-owned company, where repayment is either made directly in natural resources (in kind) such as oil or minerals, or from a resource-related future income stream. Angola is the biggest recipient of Chinese loans on the continent. Following the end of the civil war in 2002, Chinese lenders disbursed loans by using future petroleum revenues as a guarantee for repayment. They loaned Angola $42 billion—over a quarter of total Chinese lending to the African continent during the 2000–2018 period. The RBLs supported the infrastructure boom following the war—roads, ports, telecommunications, housing, power plants, etc. The model worked until oil prices began coming down. In 2016, after oil prices fell from $115 per barrel to less than $50 per barrel, Angola fell into a recession and its economy contracted for five straight years. With the Covid-19 pandemic, Angola narrowly managed to avoid a debt default. The outstanding loans to China amount to $18 billion and account for 40 percent of Angola’s external debt. Angola was the fifth-largest oil supplier to China in 2021, with as much as 72 percent its exports going to China that year. The RBL approach from China has been met with significant hesitancy by other African countries, who have watched Angola struggle with the volatile oil prices, two decades of indebtedness and repeat efforts to restructure it, and the loss of sovereign decision making about their oil reserves.

The Resource for Infrastructure Model

The Sino-Congolais des Mines (Sicomines) agreement was hailed as the deal of the century when it was agreed to in 2007. It was a resource for infrastructure deal that gave Chinese firms access to cobalt, copper, and other minerals in exchange for infrastructure investments. China invested roughly $3 billion into infrastructure development in exchange for Chinese firms receiving mining rights to deposits valued at $93 billion near Kolwezi, in southeastern DRC.

Additionally, there were no requirements to practice responsible mining or protect local communities. There has been a growing consensus that “resource for infrastructure” approaches may do more harm than good. The DRC is reviewing the resource for infrastructure deal with Chinese investors out of concern that some mining contracts are not sufficiently benefiting the country. Simply put, African countries see these as bad deals—$3 billion of investments for access to $93 billion of resources—and it leaves them in a very disadvantageous position while also preventing them from giving extraction rights to the bidder that brings them most lucrative offer, both in terms of price and non-monetary benefits such as sound environmental, social and government (ESG) practices and upstream investments.

Human Rights Violations

There have been a number of high-profile reports and incidents that have flagged human rights concerns in mining operations owned by Chinese firms. Researchers at the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre recorded 102 violations of human rights and environmental laws at 39 Chinese mines in 18 countries between January 2021 and December 2022. The Zimbabwe Environmental Law Association has flagged that miners working for Chinese firms receive low wages and go months without wages, and that consequences for speaking out can be fatal.

In 2022, U.S. Representative Chris Smith (R-NJ) chaired the Tom Lantos Human Rights Commission (TLHRC) hearing, “Child Labor and Human Rights Violations in the Mining Industry of the Democratic Republic of Congo.” The hearing included powerful testimony from Hervé Diakiese Kyungu, a well-known Congolese civil rights attorney. He confirmed the use of child labor at the Kasulo deposit and elsewhere, calling enforcement methods China’s “new way of colonization”: “Two persons identified as Chinese citizen[s]… instructed two Congolese military officers to whip two Congolese who were found on their site.” African leaders are rightfully hesitant to enter partnerships with countries and firms that have a track record of human rights abuses.

The fallout of Angola’s decades long struggle with RBLs, the DRC’s imbalanced resource for infrastructure deals that have shortchanged it billions of dollars in minerals, and the plethora of high-visibility human rights violations, have eroded decades of advances China has made on the continent. There has been a growing consensus that exclusively partnering or over-relying on China may undermine African countries own resource sovereignty.

There is evidence that some African countries are moving away from a mining sector dominated by Chinese firms. There have been significant investments from Australian, Japanese and British, and U.S. mining firms in the region in the last 18 months. It is not too late if the United States is willing to invest in partnerships with African countries. Countries are actively seeking out partnerships with diversified partners, particularly for financing and technical expertise for value chain development, to maximize their benefits from the green energy transition.

___

Gracelin Baskaran is research director and senior fellow with the Energy Security and Climate Change Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C.