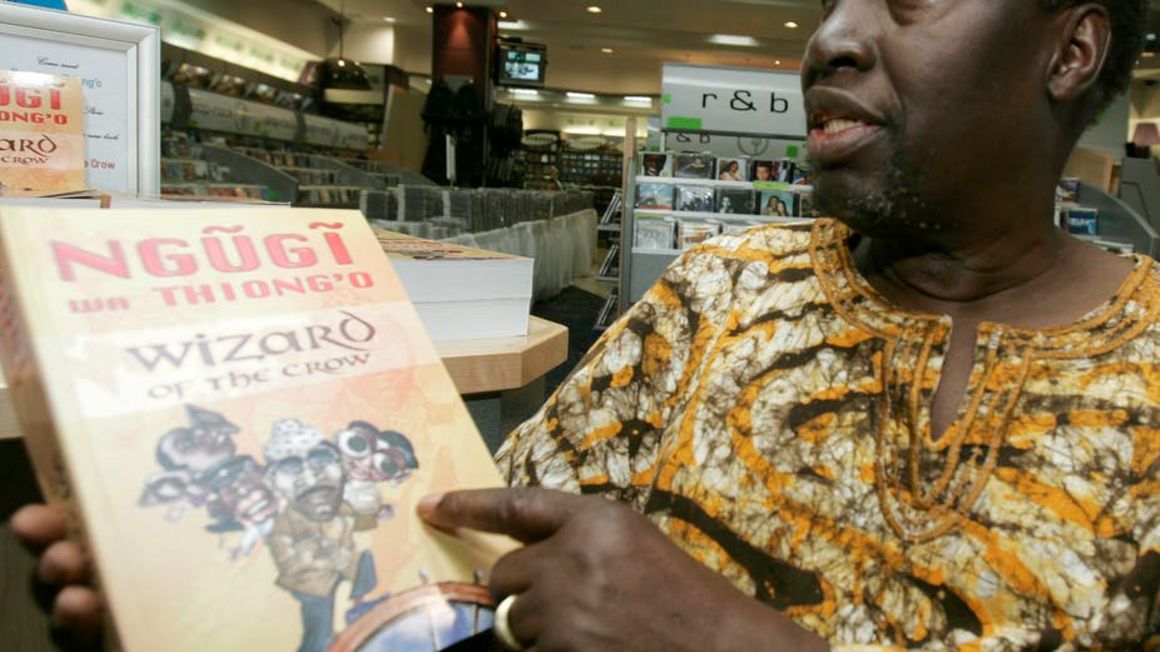

Kenyan author Ngugi Wa Thiong’o shows his newly released book “Wizard of the Crow” during launch at a Nairobi bookshop.

Kenya’s most celebrated author Ngugi wa Thiong’o turned 84 on January 5. Having published his first novel – Weep Not Child – in 1964, Ngugi remains active in writing and teaching. His latest creative effort is Kenda Muiyuru (The Perfect Nine), a Gikuyu epic that was longlisted for the 2021 International Man Booker Prize. Kenyan academic and writer Peter Kimani sets out the five things you should know about one of Africa’s greatest living writers.

Who is Ngugi wa Thiong’o?

Ngugi wa Thiong’o is regarded as one of Africa’s greatest living writers. He grew up in what became known as Kenya’s White Highlands at the height of British colonialism. Unsurprisingly, his writing examines the legacy of colonialism and the intricate relationships between locals seeking economic and cultural emancipation and the local elites serving as agents of neo-colonisers.

The great expectations for the new country, as captured in Ngugi’s seminal play, The Black Hermit, anticipated the disillusionment that followed. His fiction, from the foundational trilogy of Weep Not, Child, The River Between and A Grain of Wheat, amplify those expectations, before the optimism gives way in Petals of Blood, and is replaced by disillusionment.

African fiction is fairly young. Ngugi stands in the continent’s pantheon of writers who started writing when Africa’s decolonisation gained momentum. In a certain sense, the writers were involved in constructing new narratives that would define their people. But Ngugi’s recognition goes beyond his pioneering role: his writing resonates with many across Kenya and Africa.

One could also recognise Ngugi’s consistency at churning out high-quality stories about Africa’s contemporary society. This he has done in a manner that illustrates his commitment to equality and social justice.

He has done much more in scholarship. His treatise, Decolonising the Mind, now a foundational text in post-colonial studies, illustrates his versatility. His ability to spin the yarns while commenting on the politics that goes into literary production of marginal literature is a very rare combination.

Finally, one could talk about Ngugi’s cultural and political activism. This precipitated his yearlong detention without trial in 1977. He attributes his detention to his rejection of English and embracing his Gikuyu language as his vehicle of expression.

Works that best illustrate his thinking

It’s hard to pick a favourite from Ngugi’s over two dozen texts. But there is concurrence among critics that A Grain of Wheat, which was voted among Africa’s best 100 novels at the turn of the last century, stands out for its stylistic experimentation and complexity of characters.

Others consider the novel as the last signpost before Ngugi’s work became overly political. For other critics, it’s Wizard of the Crow – which came out in 2004, after nearly two decades of waiting – that encapsulates Ngugi’s creative finesse. It utilises many literary tropes, including magical realism, and addresses the politics of African development and the shenanigans by the political elite to maintain the status quo.

His lasting contributions to African literature

Without a doubt, Africa would be poorer without the efforts of Ngugi and other pioneering writers to tell the African story. He is also an important figure in post-colonial studies. His constant questioning of the privileging of the English language and culture in Kenya’s national discourse saw him lead a movement that led to the scrapping of the Department of English at the University of Nairobi and replaced by the Department of Literature that placed African literature and its diasporas at the centre of scholarship.

Ngugi is still active in writing. Among his recent offerings is the third instalment of his memoir, Birth of a Dreamweaver that looks back on his years at Makerere University in Uganda. This is the period when he published his novels, Weep Not, Child and The River Between, while still an undergraduate. Also at this time he wrote the play, The Black Hermit, which was performed as part of Uganda’s independence celebrations in 1962.

Presently, Ngugi is at work restoring his early works into Gikuyu, from the English language, which he bid farewell in 1977, opting to write in his indigenous language.

His work has been translated into more than 30 world languages.

Ngugi has yet to win the Nobel Prize in Literature

Ngugi has appeared on the list of favorites to win the Nobel Prize in Literature for a number of years now. Since the workings of the Nobel award committee remain secret —- the list of the committee’s deliberations are kept secret for 50 years – it will be decades before we know why he has been overlooked until now.