ERIC TOROKA

In many ways the modern economy of Tanzania was

built by the Asian immigrants who arrived from the

west coast of India over a period of four hundred

years, albeit with a huge influx from the late 19th

century.

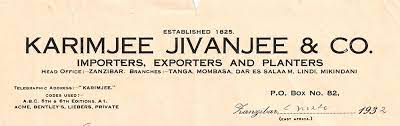

There are only a very limited number of accounts of

this story, and even fewer which focus on the history

of our successful extended family. Dr. Gijsbert Oonk

of Erasmus University, Rotterdam has told the story

of the Karimjee Jivanjee family of Zanzibar and

Tanzania, in an intriguing book.

The book, published by Amsterdam University Press,

carries a fascinating array of photographs from the

mid-nineteenth century onwards. The writer himself,

Oonk, is a broader historian of Indian migration to

Africa and, thus, very able to place this remarkable

saga in context.

Buddhaboy Noormuhamed of Mandvi, Gujarat sent

his son Jivanjee to Zanzibar where he opened his first

shop in 1818, initiating a series of businesses in

Zanzibar and the mainland based on the export of

commodities and the import of key industrial and

consumer goods. These were extremely productive

and profitable and are unique in having survived in

various forms to this day.

Critical forward looking decisions included the

acquisition in the early twentieth century agencies

from all over the then industrialized world. This

translates into the early investment in the sisal

industry, followed by coffee and then tea.

Then came the entry into the establishment of a motor

car distribution business in 1927 and a tourist camp

investment in the Serengeti in the late 1990s. The

leading members of the family played business,

political and charitable roles throughput the twentieth

century and continue to do so today.

There are some important and special characteristics

of this saga. First, the Karimjees emanate from the

close knit Guajarati speaking Bhora community, a

Shia group with intense community supporting

bonds. This becomes a critical factor when going into

business, especially when considering incidents like

when the founder’s younger brother lost a whole

cargo en route from India in the 1860’s. Then by the

early twentieth century, the leading family members

were unusually internationalist in their perspective,

traveling regularly to Europe and in the case of Sir

Yusufali Karimjee to Japan where in the 1930’s he

married Katsuko Enomoto.

Thirdly, while the majority of new initiatives operated

successfully, they were yet established more on the

basis of intuition than feasibility studies. For

instance, the move into sisal was triggered by a walk

shared by Sir Yusufali Karimjee and a Greek

plantation owner in Dar es Salaam in 1921.

Then, neither the Zanzibar Revolution of 1964, nor

the property nationalizations on the mainland in 1971

persuaded the family to abandon Tanzania.

Although many members left at that time, three

remained to man the motor business and agricultural

estates. This put the family in a strong position when

the Tanzania economy was liberalized in the late

1980s. Alongside this commercial success, several

family members have contributed to political progress

and major charitable projects.

In the colonial politics of Zanzibar, Tayabali

Karimjee and Yusufali Karimjee fought very

effectively against commercial decisions which

negatively affected the Indian community,

particularly in relation to the cloves business. Later

they were the main donors to the Tanzania National

Library and to the Faculty of Arts at the young

University of Dar es Salaam.

In the 1950s, Abdulkarim Karimjee played a

significant role in early nationalist movement. The

famous Karimjee Hall in Dar es Salaam is one such

input that housed the National Assembly sessions for

years. Today, it is the site for holding important

national events.

Tayabali Karimjee funded the construction of

Zanzibar’s main hospital, which strangely but true

stood for the fame of V.I. Lenin for more than thirty

years. It is still the main medical facility in Zanzibar.

The late President Nyerere was of the opinion that the

Karimjees would never leave Tanzania. He was very

probably correct. For, even if they do so physically,

they would still remain a valuable case study for any

student of Tanzania’s economic and social history.