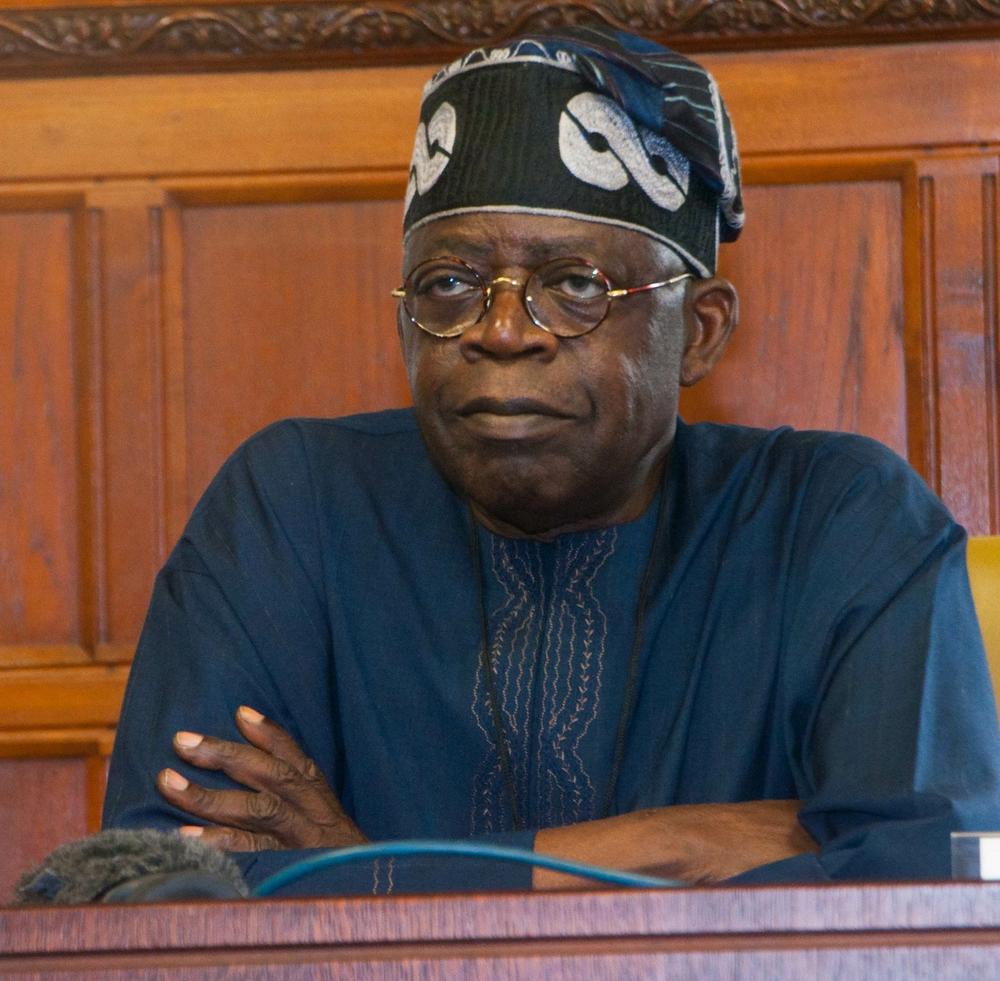

Nigeria’s president-elect Bola Tinubu has made the right noises about reform but investors should remain cautious.

Opinion by Selebia Etomi

Foreign investors may feel guardedly optimistic as Nigeria’s president-elect Bola Tinubu prepares for office, since he has professed a willingness to introduce much-needed reforms to improve the business environment. Caution, though, must be the watchword, given uncertainty over how much change he is capable of delivering.

After what many see as “the eight lost years” of Muhammadu Buhari’s tenure, when the economy floundered and investor confidence slumped, Buhari’s recently elected successor appears equipped to at least begin to raise the country’s fortunes. Not least because Tinubu, as governor of Lagos in the early 2000s, oversaw significant growth, fuelled by foreign investment, which helped to revive the creaking megacity, in particular its transport infrastructure.

Room for improvement

While Tinubu’s electoral pledges are ambitious, even if he delivers only modest economic gains he will be seen as an improvement on Buhari. On the latter’s watch, public debt mushroomed; foreign direct investment fell by over 50%; the energy sector, the backbone of the economy, saw oil majors exit, ballooning oil theft a major reason; and foreign airlines, unable to repatriate dollars, threatened to suspend operations – Emirates temporarily did so. Buhari’s cause was not helped by plunging oil prices, but his failure to appoint competent people to key positions, especially in the critical energy sector, contributed to the country’s economic woes.

Tinubu has suggested that he will loosen some of the main brakes on foreign investment in Nigeria and on overall economic performance. He clearly understands what the challenges and bottlenecks are; but what’s unclear is whether he has the political will and the support to overcome them.

The list of his intended reforms includes: improving Nigeria’s baroque exchange rate regime, which creates significant uncertainty for businesses and citizens alike; corporate tax breaks; the removal of a huge fuel subsidy (costing billions of dollars) together with the plugging of tax loopholes to provide funds for priorities such as infrastructure and education; and the strengthening of governance and security in the troubled energy sector, so that Nigeria can boost oil output and begin to meet OPEC quota targets.

All these are sensible and promising, though previous leaders have promised such and similar reforms with limited results. And if the president-elect is serious about implementing his plans, he will have to overcome powerful vested interests that benefit from the status quo.

Though Tinubu is vague on how he would stabilise the naira, he says he plans to work on this with the central bank, which may resist significant reform of the country’s multiple exchange rates.

The fuel subsidy keeps petrol cheap: plans to remove it would be deeply unpopular among Nigerians and face pushback from politicians benefiting from subsidy-related fraud. And a crackdown on oil theft in the Niger Delta, without measures to encourage economic development in the region, might spark local unrest – the last thing Abuja needs, as it struggles to quell an Islamic insurgency in the northeast of the country and herder-farmer conflicts in central Nigeria.

Problems with patronage

There are also question marks over Tinubu’s stated intention to place specialists in key positions to oversee the changes he has planned. In the oil industry, that would mean him hiring people with technical expertise to institute proper governance and controls – a clear break with his predecessor, who appointed himself petroleum minister, despite having little knowledge of the sector.

Yet while the president-elect appointed technocrats when governor of Lagos between 1999 and 2007 – better managing its finances, public services and transport system – he also acquired a reputation for political patronage. Dubbed the “godfather”, he exerted influence over the city even after he stepped down, and provided critical support for Buhari in both his successful presidential bid in 2015 and subsequent re-election four years later. Tellingly, Tinubu’s campaign slogan in his run for office in February was “It’s my turn now”.

And now, in power, will he reward friends and allies, or fulfil his pledge to appoint those with the requisite experience and expertise? Just as importantly, if he does the latter, will he be able to replicate his much-cited successes in Lagos on a national scale?

Some sceptics would argue that when he ran Nigeria’s commercial capital, the oil price was high, and the country was experiencing an investment boom. Therefore, they say, it’s hard to determine the extent to which his policies or the country’s favourable business environment drew in the funds that allowed him to revitalise the city. The situation today is very diffident: Tinubu is taking the helm just as the country faces an economic slowdown, with oil prices set to decline in the second half of the year and a debt-service-to-revenue ratio of about 80% leaving little fiscal room for manoeuvre.

While the financial prospects do not look good, Tinubu will want to make a positive impact, otherwise his authority could come under scrutiny. He won just 37% of the vote in an election in which only 29% of the electorate participated. Moreover, claims of irregularities have led to the outcome being challenged in the courts. Quick economic wins might be key to bolstering his legitimacy among investors and voters, particularly those who favoured Tinubu’s more market-friendly election rival, Peter Obi.

Tinubu has made the right noises about reform, and does have a decent administrative record, raising hopes among some of an economic recovery supported by foreign investment down the line.

Investors will probably be relieved to see the curtain fall on Buhari and encouraged that his successor recognises the problems besetting the economy. But their investment decisions will likely be influenced by how he tackles them – an early indication of which will be the competence of those he appoints to key administrative posts.

___

Source here