A quarter of 258 observed rivers had unsafe levels of at least one drug. The findings raise concerns about Earth’s aquatic life and the global threat of antimicrobial resistance.

Many of us take medicine, whether to fight an infection or get rid of a headache. Our bodies don’t fully break down many of these drugs, and they pass through our systems and into our wastewater. Leaky pipes leach pharmaceuticals into rivers and streams before they can be removed at wastewater treatment facilities. Those facilities are often inefficient and overburdened. That doesn’t even get into all of the unused medication that gets tossed.

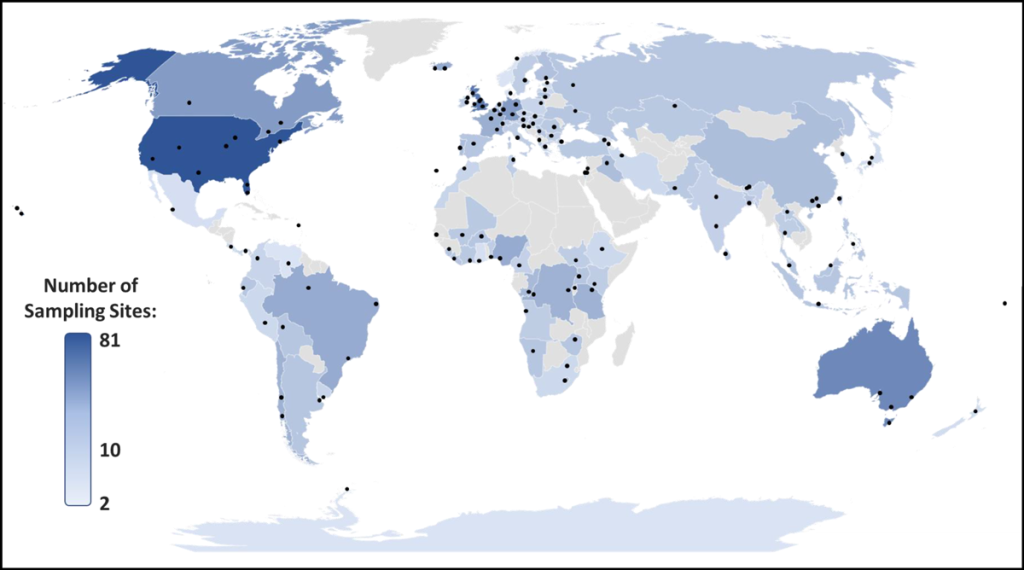

Now, a team of more than 100 scientists from all over the world has shown that the drugs we take are coursing through rivers on every continent—even Antarctica.

The study, published earlier this year in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, reported the concentrations of 61 pharmaceuticals or their residues in rivers in more than half of the world’s countries. The drugs they found ranged from antibiotics like trimethoprim to more common substances like caffeine and nicotine.

A quarter of the rivers monitored had at least one drug whose concentration either exceeded the safety threshold for aquatic life or potentially boosted bacteria’s resistance to observed antimicrobial medications. Antimicrobial resistance was responsible for the deaths of around 5 million people in 2019, according to one analysis published in The Lancet, and is among the World Health Organization’s top global health concerns. The new study found that riverine antibiotic concentrations most frequently exceeded safety thresholds in South America and Africa.

“The environmental component of this antimicrobial resistance is more significant than we originally thought,” said John Wilkinson, an environmental toxicologist at the University of York and the study’s lead author.

Apples-to-Apples Comparison

Many countries with sites monitored in the study (including India, the United Kingdom, and the United States) engage in regular monitoring and analyses, although a third have never been monitored before.

In addition to the study’s large scope, “the strength of the paper is the fact that they used a single method to analyze all of these samples from all over the world, so they can compare locations apples-to-apples,” said Susan Glassmeyer, an environmental chemist at the U.S. EPA who was not involved in the study.

Wilkinson and his colleagues started by measuring all of the river samples with the same sophisticated device, a mass spectrometer with high-performance liquid chromatography. They then standardized the sample collection process itself. The University of York researchers mailed sampling kits containing the exact same materials to all of their collaborators around the globe. They even made instructional videos to ensure that everyone sampled their local river the same way, said Wilkinson.

Lower- to Middle-Income Countries Are Most at Risk

Results showed that areas with the highest concentrations of pharmaceutical pollution in their rivers were not in the poorest countries monitored. Those areas, authors pointed out, still lack widespread access to medication.

Instead, regions with the highest concentrations of pharmaceuticals in their rivers were lower- to middle-income countries, where the pharmaceutical industry is rapidly expanding and widespread access to medication is relatively new. The highest cumulative concentrations were observed at sites in Lahore, Pakistan; La Paz, Bolivia; and Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

Regulations on pharmaceutical disposal haven’t kept pace in many lower- to middle-income countries, said Jackson Mukonzo, a pharmacologist at Makerere University in Uganda who was not involved in the study. The lag may be partly due to concern that overly strict regulations could hinder access to these life-saving medications, said Mukonzo. Residents in many of these countries, including Uganda, can buy antibiotics over the counter, leading to potential overuse and indirect pollution.

At the same time, many of these countries (as well as high-income countries like the United States) also lack adequate wastewater treatment infrastructure. Advanced treatments, like exposing wastewater to high levels of ultraviolet light, are often too expensive. “It’s unfortunately convenient for many people to just dump [pharmaceuticals] down the drain or dump [them] into a river outside with a big pipe,” said Wilkinson.

Although the new study has unprecedented scope, large swaths of the world remain unstudied, such as northern Africa and regions in central and southeastern Asia. The public and environmental health risks are not localized, however, experts said.

“Pharmaceutical residues in the environment, as well as other factors that could lead to antimicrobial resistance, should be looked at as a global problem,” said Mukonzo. “If we do not have adequate control in one part of the globe, it is still a problem for all of us.”