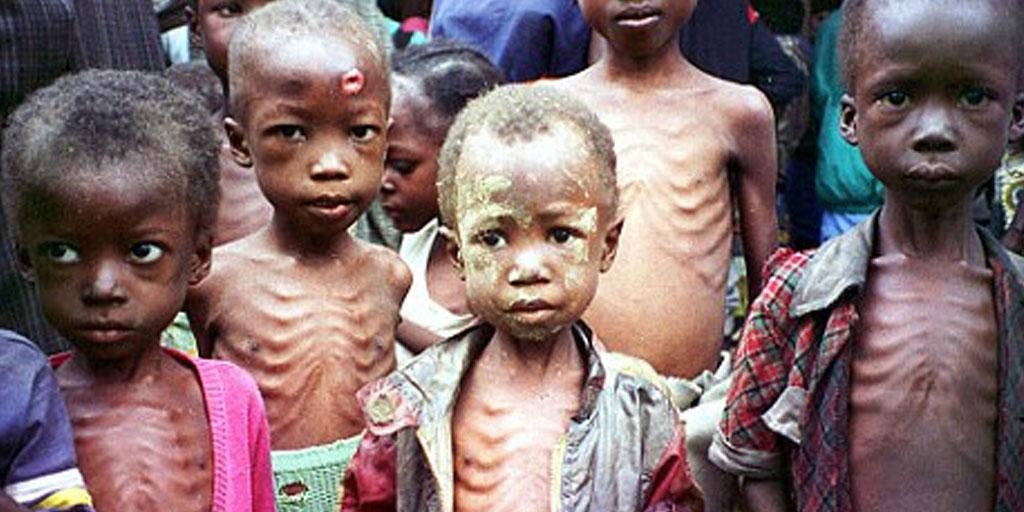

| East Africa is currently experiencing the devastating impacts of climate change, with concurrent emergencies like drought and floods across the region leading to mass displacement and severe hunger |

| LONDON, United Kingdom, More than 260,000 children aged under five may have died from extreme hunger or related diseases in East Africa since the start of the year, according to new analysis by Save the Children. Using data compiled by the UN, Save the Children evaluated mortality rates for untreated cases of severe acute malnutrition in children under five across eight countries in East Africa[i]. Using a conservative estimate, the humanitarian aid agency discovered that about 262,500 acutely malnourished children may have died between January and November 2021[ii]. East Africa is currently experiencing the devastating impacts of climate change, with concurrent emergencies like drought and floods across the region leading to mass displacement and severe hunger. While communities in eastern Kenya, southern Somalia, and parts of Ethiopia are reeling from successive drought, parts of South Sudan remain underwater after three years of unpredictable and excessive rains. Health centre admissions of children suffering acute malnutrition have risen dramatically in 2021, with a 16% increase in the first half of this year from an already high baseline. Severe acute malnutrition is the most extreme and dangerous form of undernutrition. Symptoms include jutting ribs and loose skin, with visible wasting of body tissue; or swelling in the ankles, feet and belly as blood vessels leak fluid under the skin. Currently, less than half of acutely malnourished children (46%) across East Africa are being treated for the condition[iii]. Akuol*, 16, the mother of 17-month-old Abdo* in Bor, South Sudan, has struggled to get enough food for herself and her son. The delivery of the humanitarian supplies she usually relies on has recently been hampered by heavy rains’: “There is nowhere I rest comfortably, no food (no grains, no oil) and the house we are living in is like living on the street. I have no one to turn to for help, sometimes I go and beg to people at the riverside and buy food to eat if I am lucky to get something. We have no food to eat, we wait for humanitarian support and when it is finished we stay without food. For the period that we are waiting for the next ratio (food distribution), we remain without food and that is how the situation is for us. “There is food shortage because when it rains it is difficult for humanitarian food to be brought to us and distributed.” Kijala Shako, Director of Advocacy, Communications, Campaigns and Media for East and Southern Africa, said: “We are devastated that some 260,000 children across East Africa may have died of hunger since the start of 2021. In a year that saw the COVID-19 pandemic continue to wreck lives and economies, and conflict kill and displace thousands of families, it has been the impacts of the climate crisis that have ultimately taken the highest toll on children. “At COP26 last month, high-income countries and historical emitters had the opportunity to support the development of funds to address rapidly escalating loss and damage. Unfortunately, they missed the boat. Today’s shocking figures tell the human story behind what we are calling for. “Deaths from hunger are not inevitable and we have the tools, skills and experience to reach children and their families before it’s too late. Countries that are bearing the brunt of the climate crisis must be supported for the damage that is already being done – that they themselves have played a very little part in creating. It is vital that we see the creation of a new climate finance mechanism for loss and damage by 2023. At the same time, we also need to see a drastic reduction in fossil fuels to limit warming temperatures and reduce these kinds of disasters.” Save the Children is calling on governments to fully fund humanitarian response plans, and support social protection schemes and health and nutrition services for children, including the treatment of acute malnutrition. Globally, malnutrition is linked to nearly half of all under-five deaths. In 2020, 149 million children were stunted (too short) and 45 million children were wasted (too thin). Without fast and decisive action from the global community, an additional 3.6 million children around the world will become stunted by 2022 and an additional 13.6 million children wasted because of the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. The organisation is urging donors to prioritise humanitarian cash and voucher assistance for families, and focus on the increased risk of violence—particularly gender-based violence—caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, only by ending global conflict, tackling changing climate and food systems, and building more resilient systems and communities will future similar disasters be averted. [i] Burundi, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan and Uganda [ii] Based on an analysis of publicly available UN data including HNOs, the Nutrition Cluster, UNICEF, IPC and FSNWG estimates ranging between January and November 2021, 2,390,279 children under the age of five across the eight countries needed treatment for Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM) between January and November 2021. The estimate of 262,514 deaths represents the mid-point of an estimate range for mortality in cases of untreated SAM, based on longitudinal studies and an average Middle Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC) of severely malnourished children. The lowest level is 183,701 deaths, assuming a MUAC of 110mm. That rises to 341,327 when MUAC is assumed to be 106mm. The mid-point is 262,514 deaths from SAM between January and November 2021. [iii] Based on an analysis of publicly available UN data including HNOs, the Nutrition Cluster, UNICEF, IPC and FSNWG estimates ranging between January and November 2021, 1,272,607 children under the age of five across the eight countries are not being treated for SAM. This represents 53% untreated / 47% treated. |